Following the earthquake, Haiti’s caregivers found they needed to focus on

the basics of healing acute and chronic wounds.

With a nurse-in-training in tow, Emerson Germain makes his way around the spinal cord injury unit at Hospital Bernard Mevs Project Medishare in Port-au-Prince, stopping to change the compression bandages on a woman paralyzed in an accident.

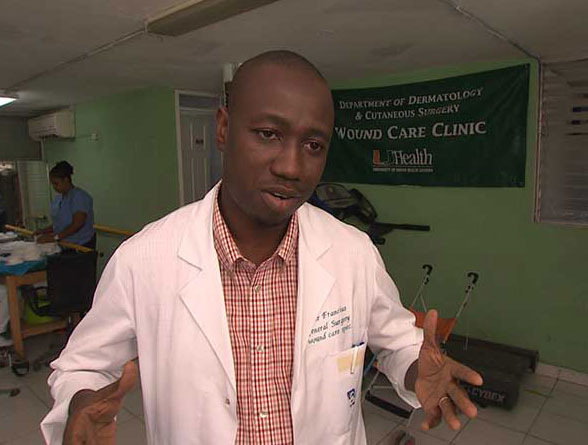

Haitian surgeon Adler Francius eased his own pain by learning a new specialty—wound care—after the earthquake.

As often happens with immobilized people, she has a pressure ulcer on her leg, but with the right dressings and the infection control and pressure-reduction techniques Germain demonstrates to the nurse, the bedsore is shrinking.

Five years after the former business owner lost his family and his hair salon in the earthquake, Germain has found a measure of solace and new purpose as a wound care technician. It is a specialty that did not exist in Haiti before the disaster underscored the need to train Haiti’s health care work force in the basics of healing acute and chronic wounds, and the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine’s John Macdonald stepped up to fill the void. .

Within days of the catastrophe, Macdonald, professor of dermatology and cutaneous surgery and founder of the World Alliance for Wound and Lymphedema Care (WAWLC), set up the world’s first post-disaster wound care center at UM/Project Medishare’s field hospital in Haiti. Today, with support from the Miller School of Medicine’s Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, he continues to guide the Caribbean’s only holistic wound care program at Bernard Mevs, where a surgeon and five technicians treat as many as 80 wound patients a day.

“I am proud of what I am doing,” says Germain, who initially managed his grief by working as a patient transporter at the field hospital UM/Project Medishare opened days after the earthquake. “I have a lot of knowledge about wound care. It helps me to help other people.”

Although 80 percent of the earthquake survivors at the tent hospital had crush injuries with open wounds, Germain would soon learn that chronic wounds are often associated with disease, rather than disaster. In fact, venous leg ulcers, caused by poor circulation, are the most common type of chronic wound, and diabetic foot ulcers the leading cause of amputation in Haiti. Both are growing epidemics around the world.

I had so much pain with the loss of my daughter, my sister, and my cousins, and now I find healing people helps me heal myself.

Yet, even promising surgical residents at Haiti’s public hospital, like Dr. Adler Francius, now the director of Bernard Mevs’ Wound Program, didn’t know wounds require a comprehensive approach to remove dead tissue, reduce pressure, control swelling, and keep the sore moist—not dry as many surgeons are taught. He didn’t realize wound care was even a specialty until he attended a seminar on the fundamentals of wound care that Macdonald and WAWLC vice president Terry Treadwell organized and taught in Haiti after the tent hospital closed.

“As a surgeon, I treated wounds all the time, so I didn’t understand why training in wound care was necessary,” says Francius, who was the first surgeon selected from the seminar for a fellowship at Treadwell’s Institute for Advanced Wound Care in Alabama. “I didn’t know how much knowledge I was lacking. The way we do it is way different than a surgeon. This is the only place you can find what I call the holistic approach. We treat the whole patient.”

With Dr. John Macdonald’s vision and guidance, knowledge of wound care is spreading in Haiti.

Some of those patients are in the hospital, with surgical, trauma, or other wounds. But the overwhelming majority are day visitors who fill the benches, lean against the walls, and spill into the courtyard outside Bernard Mevs’ outpatient clinic, waiting to have their wounds cleansed and dressings changed. For those who cannot afford to pay, their care is free, underwritten by a Canadian benefactor who supports Macdonald’s mission. But they are still asked to pay $1 for their bandages.

It is a dear sum in Haiti, equal to the average daily wage for many workers. But as Francius notes, patients who pay it are more engaged in their own care and more likely to follow the instructions that will help them heal—and in doing so continue to help their healers heal. Like Germain, Francius suffered his own devastating losses in the earthquake. His oldest daughter and his sister, who was studying medicine, perished in the disaster along with several cousins.

“I had so much pain with the loss of my daughter, my sister, and my cousins, and now I find healing people helps me heal myself,” Francius says. “They helped me find something meaningful.”

He also found a father figure in Macdonald, who with his white beard, Francius jokes, looks a lot like Santa Claus. But for Francius, and for Haiti’s small but growing contingent of wound care specialists, the comparison goes far beyond appearance. As Francius notes, Macdonald has given Haiti a precious gift.

“His work is not well known, but it has had a huge impact,” Francius says. “Thanks to his vision, we are spreading knowledge of wound care. Now wound care is a specialty and more Haitian doctors are able to take care of wounds. We should believe in our ability to take care of ourselves.”