A University of Miami senior is working to establish an annual summer camp to empower young Haitians to be change agents.

They stood in a loose circle on a patio at a community center in Saint-Marc, a coastal port town about an hour north of Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince. The Haitians, mostly teenagers and young adults, sang songs, smiled, and laughed as they introduced themselves to each other and the visitors from Miami.

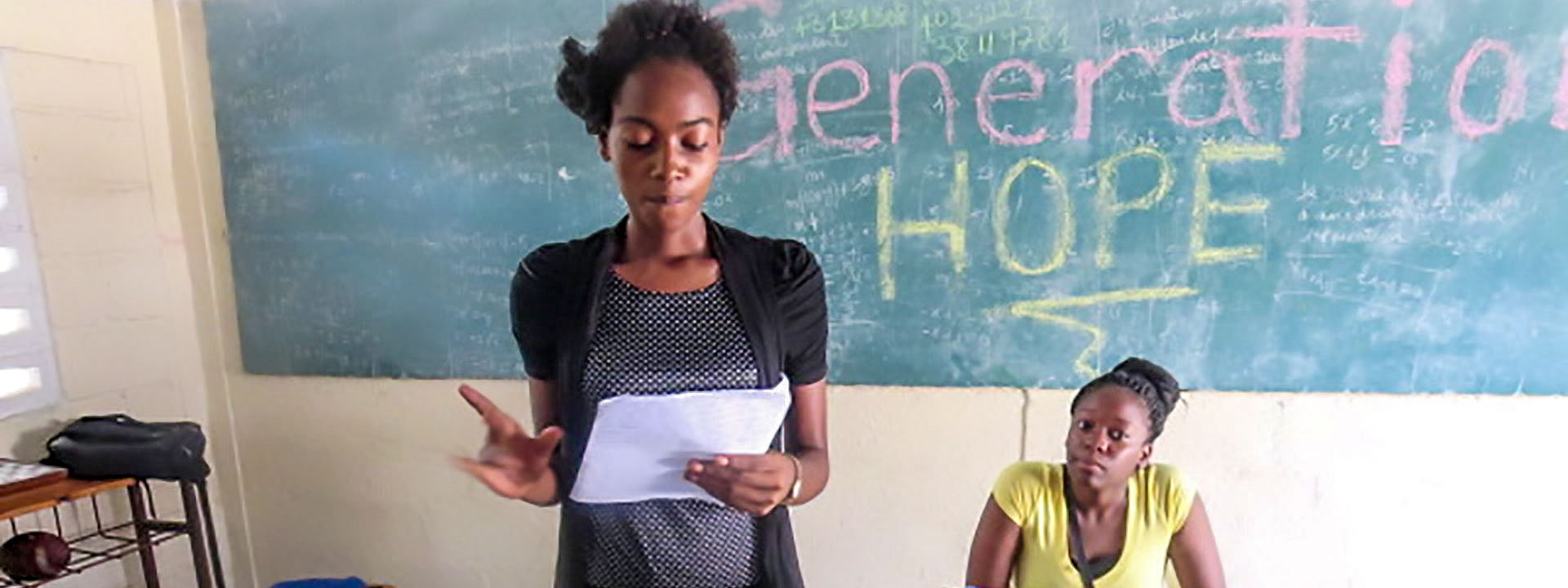

Generation Hope founder Guerdiana Thelomar

Guerdiana Thelomar looked on with a sense of pride and happiness as her brother, Jean Herby, videoed the event.

It was July 2014 and the start of the first summer camp of Generation Hope, a project Thelomar launched at the University of Miami to help empower young Haitians to become agents of change in their communities and help them discover their own passions.

“Despite everything that is going on, there are young people, young Haitians, who still believe in themselves and still believe in their country,” Thelomar said. “There is hope.”

Thelomar has a passion to serve and help people, as witnessed by her actions around campus. She holds leadership roles on the UM Butler Center for Volunteer Service and Leadership Development Student Advisory Board, the Women’s Leadership Symposium, and the Black Awareness Month Committee. As a resident intern at the UM Wesley Foundation Campus Ministry, she helps coordinate service trips to Haiti for UM students as well as leads a weekly small Bible group.

Thelomar, who is majoring in Human and Social Development and Visual Journalism, is also president of Planet Kreyol, a Haitian student organization on campus. One of the main goals of the student group is to educate people about the Haitian culture.

Within these organizations and many more, Thelomar strives to bring people together to learn from one another and grow together.

Thelomar has been visiting Haiti since she was in third grade. Her father and mother, Jean Claude and Guerda, are from Saint-Marc. They moved to Miami in 1992. The family was in Haiti for a visit just a short time before the January 12, 2010 earthquake struck.

Thelomar was in the car in Miami with her father, listening to a Creole radio station, when news of the earthquake reached them. The radio announcer spoke of the “tranbleman de te,” which means trembling earth – a phrase Thelomar had never heard before and asked her father to translate. They tried to call family members in Haiti, but couldn’t get through.

For days following with earthquake, Thelomar’s family stayed glued to the television news for the latest updates. The death toll continued to rise. They cried together as they heard about friends who had lost loved ones.

“We helped each other get through it,” she recalled. “We didn’t turn the TV off. Since the earthquake, there was a reawakening, sort of like a candle that reignited in me. I had a stronger passion and drive to not only learn more about my culture and my people but also to share my knowledge and my senses with other Haitian Americans here in Miami.”

“One guy said to me, ‘In Haiti you don’t dream.’ I felt really moved, and I just kept thinking about how I could have been in that situation. I wanted to help them grow and have faith in themselves,” she said.

The idea for Generation Hope was born.

With funding and help from the Butler Center and the Clinton Global Initiative University, Thelomar was able to get Generation Hope off the ground. She wants it to be an annual, three-day summer camp. The ultimate goal is to have young Haitians carry the torch and sustain the event themselves.

During the July 2014 camp, the groups brainstormed ideas and worked on projects that promoted change and empowerment. One young man wrote a song about hope. Another group worked on a plan to sell household goods, such as laundry soap.

“They felt young people in Haiti need jobs, so they wanted to start a business,” she said.

Thelomar traveled to Saint-Marc for the inaugural Generation Hope camp with her parents and older brother, Jean Herby. There were three groups of Haitians from different neighborhoods at the camp. As an icebreaker, they sang songs and made some dance moves as they introduced themselves.

“What we’re trying to teach is sustainability. One of the main objectives of the summer camp is for young Haitians to believe in themselves and believe that they can be the change agents in their own communities. They have the power to do it themselves,” Thelomar explains.

Thelomar is also involved as a research assistant with the Haiti Legacy Project, which is spearheaded by Associate Professor Guerda Nicolas in the School of Education and Human Development. The Haiti Legacy Project is a one-stop virtual space where teachers, students, and anyone anywhere in the world can browse a wealth of information, articles, news, and other resources not only about Haiti’s slavery, colonization, revolution, and independence, but about the song, dance, music, art, and literature that is such a vital part of the beleaguered nation’s rich cultural heritage.

“Haiti has always been a part of me, and who I am and what I do,” Thelomar said.

In addition to Planet Kreyol, which has about 50 members and is planning a candlelight vigil and fundraiser to mark the five-year anniversary of the earthquake, there are a number of other student organizations and study abroad opportunities at the University of Miami that have touch points with Haiti, both before and after the earthquake. UM students have participated in service projects in Haiti over spring break. Medical students have done capstone projects on the island. Nursing students help staff mobile clinics that travel to rural areas. Anthropology students study the culture and work to grow communities.

Some have turned to art to tell the story of the island. Haitian-American Rachelle Salnave is one of them.

Salnave had never been to Haiti before the earthquake. But as she observed the devastation, and the resilience of the people, the then-School of Communications Motion Pictures major was inspired to create a full-length documentary on Haiti as her thesis project.

“As tragic as the earthquake was, it has allowed people to look at Haiti in a different way,” she said.

Salnave’s mentors for her documentary project included School of Communication Associate Professors Ed Talavera and Grace Barnes, and College of Arts and Sciences Assistant Professor Louis Herns Marcelin, among others.

Salnave explains, “I had the opportunity to go to L.A. or New York for film school, but I chose Miami because of its connection to Haiti. Plus, I loved the Motion Pictures program.”

The documentary La Belle Vie (The Beautiful Life) is about the journey to discover Salnave’s roots by examining the complexities of Haitian society—both political and economic. Using her personal family stories interconnected with the voices of people on the island, the film chronologically uncovers the rationale behind the country’s social class system and how it has affected the Haitian-American migration experience. The film’s underlying message beckons everyone to work as one to rebuild a new, stronger Haiti.

The documentary is currently being showcased in the U.S., France, and Canada, and elsewhere.

“My mom always used to talk about ‘la belle vie’—this beautiful life in Haiti,” Salnave said. “Growing up in Harlem in a two-bedroom, cooped-up apartment, I didn’t live the charmed life that my grandparents and mother had in a younger Haiti. As a kid, I wanted to live that ‘beautiful life.’ Years later, when I finally edited the film, I realized that the good life for me is seeing Haiti rise and for all of us to do it together.”