The University of Miami’s School of Architecture has a strong and important relationship with Haiti to assist in design strategies and building community.

On her first trip to a post-earthquake Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Sonia Chao, an architect accustomed to using her design and planning skills to help lift neglected communities out of despair, toured a housing development built by one of the many nonprofits that rushed to the country’s aid in the wake of the devastating 2010 temblor.

Well built and spacious, the homes were more than adequate to house some of Haiti’s displaced residents. But there was only one problem: The homes stood vacant. No families. No couples. No children running around at play.

“It didn’t make sense,” Chao, a University of Miami School of Architecture faculty member, recalled of her visit to Haiti in 2012 with a team of other architects. “What suddenly spoke very loudly to us was that the project was imported. The Haitian people had no connection to it. The homes were in a grid pattern that didn’t have anything to do with quality of life and were missing many of the aspects that make a community.

“It was a lesson,” Chao says, “that anything imported and not homegrown won’t work, which is why this process is so important.”

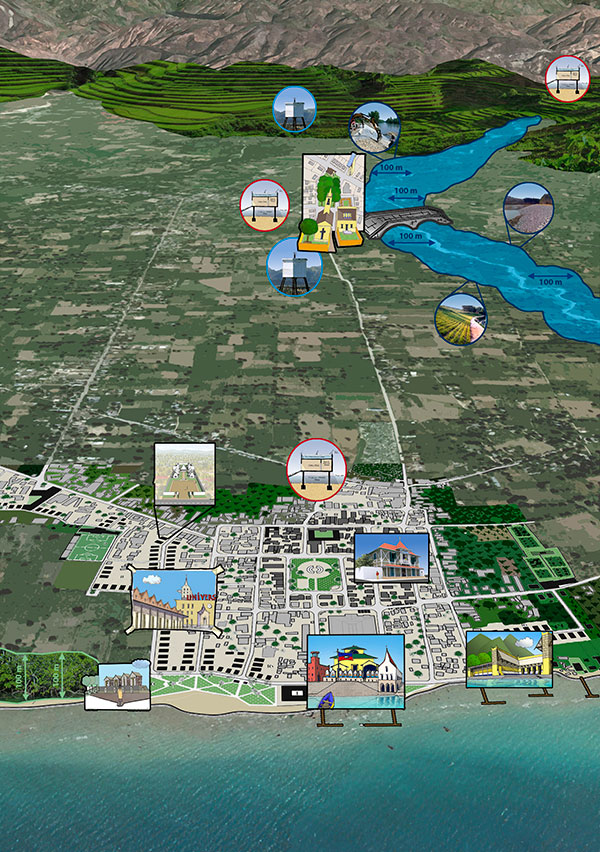

The process to which Chao refers is her grant-funded endeavor for devising strategies to decentralize a still densely populated Port-au-Prince and develop the rural and coastal towns, villages, and hamlets that lie about 20 miles north of Port-au-Prince in Akayè Commune, the country’s breadbasket.

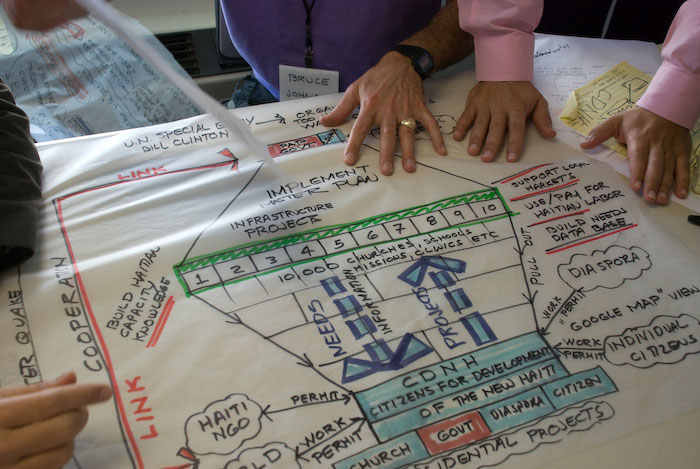

Since late September 2012, Chao and her team of architects, civil engineers, and planners have taken at least four trips to the region, meeting with government officials and, more important, engaging locals during a series of planning sessions to find out how they want to re-imagine and reshape their communities.

“We asked them to write down what we call the SWATs—strengths, weaknesses, assets, and threats—of their communities, and to draw pictures of where they currently live and how they would like to live,” explained Chao. “They made some beautiful drawings. Even the children got involved.”

Among the ideas residents and architects came up with for cultivating Akayè: micro-businesses such as markets and bed-and-breakfasts, schools, a medical clinic, and a ferry service for shuttling tourists to other towns. Consistent with Akayè’s reputation as an agricultural center, townspeople also called for more farms along existing roads.

“What they don’t want is sprawl,” said Chao. “They’re adamant about that. They don’t want to see their land gobbled up by houses.”

But as much as the people of Akayè want to see improvements, one industry they depend on for economic sustainability should cease. The production of charcoal is common in the region, with local vendors selling the carbon-containing substance mostly to people in Port-au-Prince. The production strips the country of its native trees, leaving large swaths of land prone to mudslides during the rainy season that washes away fertile topsoil. When the soil is gone, farming is impossible.

“It’s bad for the environment, and we’re trying to persuade them to abandon it,” Chao says of the charcoal industry. “It’s difficult, though, to tell someone to stop doing something when you haven’t really come up with an alternative, so we’ve proposed garbage recycling stations as an alternative.”

Akayè will also need check dams, terraced landscaping, and gabion walls built of rubble, rocks and chicken wire to help divert rushing water from flash floods, a major problem in the mountainous delta region, until larger, permanent dams can be built.

This isn’t the first time Chao has led an effort addressing ideas to decongest Port-au-Prince and build up Haiti’s northern region. Just two months after the magnitude-7.0 earthquake devastated Haiti, killing more than 200,000 people, displacing more than 1 million, and destroying the infrastructure of its capital city, Chao led a two-day charrette at UM’s School of Architecture that tackled that very subject.

The mantra is the same today as it was then—decentralization of Haiti’s overcrowded urban core is crucial, and communities in outer-lying areas need to be developed, allowing for tourism and other industries to thrive and spur economic growth.

The School of Architecture has also been involved with a number of other initiatives involving Haiti—some having begun prior to the 2010 earthquake. In June 2014, Associate Dean Denis Hector traveled to Haiti to be part of the ceremonies marking the opening of a new school in Lacolline in Haiti’s Central Plateau, a design project that began before the earthquake and involved UM faculty and students in Miami’s Carrollton School of the Sacred Heart. The School of Architecture also helped facilitate a 2012 invitation by the Archbishop of Port-au-Prince soliciting designs for a new cathedral in the nation’s capital to replace the one destroyed in the earthquake. More than 130 designs from throughout the world were submitted, and a panel of jurors led by then-Dean Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk narrowed the field to 10 finalists before selecting the winning team led by Puerto Rican architect Segundo Cardona.

This past November, Chao presented her team’s final report on Akayè to the W.K. Kellogg and Barr foundations, the two primary funding agencies of her project. She said it will take a concerted effort to ensure the initiative’s major proposals are implemented and don’t fall by the wayside like so many relief efforts before it.

Chao, who directs UM’s Center for Urban and Community Design, an initiative that has helped improve Miami-area neighborhoods like Overtown and Opa-Locka, said the proposals would aid the people of Haiti immensely. Like the little Haitian girl Chao once saw standing alone in the middle of a busy Port-au-Prince intersection, crying out for someone.

“She was tiny and couldn’t have been more than 3,” Chao recalled. “I looked at her and said to our driver, ‘We need to stop.’ But just then, the child’s mother appeared, took the girl under her arm, and disappeared into an ocean of people. I thought to myself—no one should have to endure this.”